Manxwytch is pleased to be a contributing author to the upcoming anthology on Traditional Witchcraft from Three Hands Press.

Hands of Apostasy A Witchcraft Anthology from Three Hands Press

Manxwytch is pleased to be a contributing author to the upcoming anthology on Traditional Witchcraft from Three Hands Press.

Hands of Apostasy A Witchcraft Anthology from Three Hands Press

Here is another display piece from the old Mill Museum on the Isle of Mann.

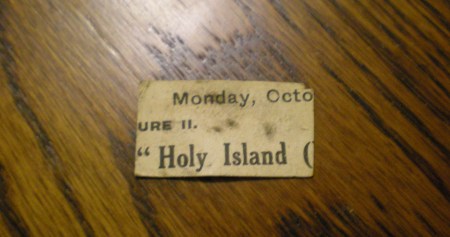

Here is a small chunk of lucky coal and a card. The card is about 1 1/2 inch long by 3/4 inch tall and the lump of coal is only a wee bit larger.

The card reads:

Lump of coal, found in the street by Miss Devean, and given to me on my return to London, “For Good Luck”

April 1917

It is written on some kind of advertisement card stock and I have reproduced a photo of the back of the card as well because I found it amusing with its reference to a “Holy Island”.

I’ve always considered coal lucky myself and if in the middle of the bleak, cold, dark, damp Winter Solstice the Devil offered me coal and St. Nick offerred me a trinket – I’d accept the Devil’s gift.

Another piece from the archives.

Again, here is Gerald Gardner’s dreawing of the Witches Mill Museum in Castletown. This time it’s not a pamphlet but made into a postcard and was another item sold in the shop to the tourists.

Honestly, this image gets a bit tiring because it was marketed so much. I expect that Gardner was quite proud of it and his idea of secret messages hidden in the image for only those who had the Wica knowledge. It’s quite easy to see the five pointed star in the stars surrounding the Witch. Also the Supernal Triangle below the Moon. There’s plenty more…

This is another intriguing display of Traditional Witchcraft, folklore and magic, from the old Witches Mill Museum.

Two sticks cut of the same length, bound with green ribbon and wax. The top stick is painted and labelled:

ASH, Coles Pits, August: 1918

The second stick is labelled

ELM, Wadley, August: 1918

The Ash and Elm are secured onto a mat board and the writing explains the charm saying:

Ash and Elm Charm, placed on a mantel shelf

To keep off Ghosts and Hobgoblins.

And in very tiny script it continues saying:

As used in Cheshire 1895.

It is a sad state of affairs that the only documentation on the web from the Isle of Mann’s national website regarding The Museum of Magic and Witchcraft is a shameful piece of rubbish that only serves to demonstrate the lack of scholarly integrity and outright distain and intolerance of the beliefs and values of those outside of the perceived social norm. That being said, I feel it is time to discuss The Museum of Magic and Witchcraft pamphlet with a more understanding view of the period, clarify errors of authors and perhaps add a more sensible response than the one from the IOM’s page written by “Katie Agnostopoulou”.

One must keep in mind, when reading anthropological, historical, folkloric and religious texts of the 19th and 20th century that the empirical methods of research which we pride ourselves upon today were only in the initial stages of being formed. Therefore research by such notable forefathers as Eliade, Durkheim, Frazer, Douglas, Weber, Moore and many others should be regarded with the respect due to the research methods they afforded at the time, valued for their unique viewpoint and the intriguing theories offered regarding the subjects, honoured for their interest and development of the field and for their passion and interest in the preservation of lore. Likewise, armchair authors, historians and insiders of cultural and religious traditions such as Gerald Gardner should also be respected with their own unique theories and faults of the time. As an insider to a reviving and developing religion, Gardner’s (and other’s) insights offer us a rare historical glimpse of the founding of a new religious movement which will later take on a life of its own and span the globe. Witchcraft the Old Religion is rising from the ashes and taking its place among what is presently termed ‘New Religious Movements’ (NRMs) and contains various pagan religions that were also ‘re-birthed’ at this time in history.

In July, 1951 Cecil Hugh Williamson along with Gerald Brosseau Gardner opened the Witchcraft Museum in Castletown, Isle of Mann. These two highly knowledgeable men possessed exceptional collections of artefacts relating to folklore, witchcraft, magic, mythology and superstition. As well, they each had their own personal contacts, and craftspeople who contributed items for the displays in the Museum. The relationship between these two men is complex and ended on bitter terms however, they both played an important role in the development of present day Witchcraft, and their contribution to the survival of various folk traditions as well as the rekindling of the love of the Old Gods and Goddesses of magic.

This is the first version of The Museum of Magic and Witchcraft pamphlet which was written by Gerald Gardner for, and along with Williamson’s input. This small sepia version which I have scanned and posted here is numbered 1 of 6 and it has been suggested that this was part of the initial prints offered by the Castletown Press for review by Gardner and Williamson prior to full publication. There are later versions of this brochure, one that is specifically Gardner’s own and one that was published by Monique and Scotty Wilson after Gardner’s death. Each brochure has its own photographic style but the wording of the pamphlet is little changed if at all.

I have placed the photo along with written text for simple viewing and commentary and have attempted to keep the text with the image provided. I am retaining the format of original text in bold and my comments in standard. You may click on any image to enlarge the view.

The Witches Mill, Castletown, I.o.M.

The cover of the pamphlet is drawn by Gerald Gardner. The original is a large pen and ink poster on hard board archived in the James’ Toronto Collection of Gardner’s papers, purchased from the Ripley Museum sale in 1987. Postcards were also made of this image and sold in the gift shop along with various other trinkets for the tourists.

THE STORY

OF

THE FAMOUS WITCHES MILL

AT CASTLETOWN, ISLE OF MAN

by G. B. GARDNER

Published for C. C. Wilson

The Witches Mill, Castletown Isle of Man

By

The Castletown Press, Arbory Street, Castletown

*

THE exact age of the old windmill at Castletown, Isle of Man, known as “The Witches Mill,” is uncertain; but we know that it was there in 1611, as it is mentioned in a court record of that date.

We know that the windmill was built in 1828. It burned down and was restored in 1848. There is no court record that accounts for the windmill in 1611 however, it is probable that Gardner misunderstood the history of the Arbory witches and confused the dates. The trials of the Arbory witches occurred in 1666 and were in Kirk Arbory.

The Mill got its name because the famous Arbory witches lived close there, and the story goes that when the old mill was burned out in 1848 they used the ruins as a dancing-ground, for which, as visitors may see, it was eminently suited; being round inside to accommodate the witches’ circle, while the remains of the stone walls screened them from the wind and from prying eyes.

There are two fundamental precepts of history that are often neglected by amateurs and historians alike. The first is that you were not there and you cannot know for certain what happened. The second, particularly in this case is that simply because something wasn’t documented doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen. And here it is important to note that the population in question, witches, were both by choice and necessity secretive about what they did and where they did it for fear of public censure and punishment.

That said, I will state clearly that the Arbory witches existed on the Isle of Mann both historically and during the period of the Mill Museum. The last known surviving Arbory witch passed away quietly on Mann in the first decade of the 21st century.

The Mill Tower was well used by the witches on the Isle of Mann. It is, as Gerald described it, “eminently suited for the witches’ circle.” A round tower with an open vault to the heavens, moon and starry sky, protected from the wind, and able to keep a warm fire lit for the dancers. It was in fact, perfect, though it was not the only site used on Mann or in the Museum for that matter!

After being abandoned for many years, the large barns of the Mill were taken in 1950 to house the only Museum in the world devoted to Magic and Witchcraft. The attractive grey stone walls of the Museum and the old mill stand in four acres of ground, thus providing a large car park, and there is an excellent restaurant on the ground floor of the building, where visitors may enjoy modern service in picturesque, old-world surroundings.

As the Museum is only a mile and a half from the Airport (5 minutes by taxi), many visitors fly over from the mainland to see the Museum only, and return the same day.

The Isle of Mann was a tourist haven in the 1950s and 1960s. It was an easy boat ride from Britain, Scotland or Ireland for a vacation not too far from home and not too costly on the purse. The Isle of Mann prided itself upon it tourist trade with its Grand Promenade in Douglas, street vendors, horse drawn trams, cinema, buggy rides, costal path and sandy beaches that at one time, some thought rivalled the shores of Southern Europe.

The policy of the Museum is to show what people have believed in the past, and still do believe, about magic and witchcraft, and what they have done, and still do, as a result of these beliefs. It contains a unique collection of authentic material, some of which has been given by witches who are still living or only recently dead. It shows how witchcraft, instead of being extinct, or merely legendary, is in fact still a living religion, and the possessor of traditions of great interest to scholars, anthropologists, and students of comparative religion and folklore. Witchcraft is actually the remains of the oldest religious traditions of Western Europe, some of which seem to have come from the Stone Age.

The idea that Witchcraft was the remains of one of the oldest religions of Western Europe was not a view unique to Gerald Gardner alone. It was part of a new theory of religious study which identified religion as evolving from a primitive past to modernity and an often hoped for secularism. Such early proponents of the evolutionary theory of religion were Max Mueller, Lucien Levy-Bruhl, Sir James Frazer, Herbert Spencer, E. B. Tylor to name a few and there were many others with similar theories. Gardner’s thoughts were clearly working within the theoretical models of his time.

Apart from the other material, the Museum also possesses a large collection of Manx bygones, including what is said to be the only known specimen of a Manx Dirk, of the type which made the Manx Dirk Dance famous; the dance still exists, but is now performed with wooden weapons.

There are many cultural dances throughout the world and the Isle of Mann also had its own dances. Though I am not familiar with the historical Manx Dirk, I can say that I have read accounts of Manx dances in historical records. Many traditional songs and dances were collected by the 20th century Manx Folklorist, Mona Douglas who did a great service to preserve Manx cultural traditions.

From time immemorial the people of the Isle of Man have been believers in fairies and witches. The celebrated “Fairies’ Bridge” is only six miles away from the Museum. There have been a number of witch trials in the Island; but it appears from the records that the favourite verdict of a Manx jury in cases of alleged witchcraft was “Not Guilty, but don’t do it again.”

The Isle of Mann holds a substantial amount of Faery Lore for such a small island. “The Fairies’ Bridge” referred to is the mock up for the tourist industry and is still in use on Mann today though now-a-days it hangs with more brassieres and notes to win the TT than with prayers to the Mooinjer Veggey. Many a coach driver had lots of fun with the tourists passing over the bridge during the heydays! The actual Faery Bridge of Manx historical legend is located in Braddan.

In reference to the “Not Guilty” verdicts of witches on the Isle of Mann, as far as modern day historians of witchcraft can find, it was a common practice in the courts and not unique to Mann. As records of the witch trials are only recently being examined, reviewed and discovered, there is no way that Gardner or those of his time period would have had this kind of information so his surprise at the leniency of the courts is simply understood.

(Please see the video at the end of this blog for an introduction to the academic study of witchcraft with a focus on historical witch trials in Great Britain).

The only recorded execution of a witch in the Isle of Man took place within a short distance of the old Mill, when in 1617 Margaret Ine Quane and her young son were burned alive at the stake near the Market Cross in Castletown. She had been caught trying to work a fertility rite to get good crops; and as this was in the time when the Lordship of Man was temporarily in the hands of the witch-hunting King James I, she suffered the extreme penalty. A memorial to Margaret Ine Quane, and to the victims of the witch persecutions in Western Europe, whose total numbers have been estimated at nine millions, is in the Museum.

The execution of Margaret Ine Quane happened under the rule of the Stanley Family who were ‘given’ the Isle by King Henry IV in 1405. The estimation of the victims of the witch craze in Western Europe is largely exaggerated. We clearly do not know the number of victims though there have been various academic guesses… none of which can be claimed with accuracy.

The memorial to Margaret Ine Quane was painted and designed by Gerald Gardner in the museum. There was also a makeshift plaque for many years that rested on the Candlestick in Castletown, outside the George Pub. It memorialized the passing of Margaret Ine Quane and though it disappeared in the 1980s, it has again resurfaced. Knowing Isle of Mann sentiments towards witches and magic I doubt it will remain there for long.

One cannot understand history without some knowledge of our ancestors’ beliefs, and what they did because of those beliefs. What manner of people were these magicians and witches ? What went on in their minds ? What was the difference between them ? These are some of the questions this Museum sets out to answer.

Ceremonial magic gave its rites a Christian form; whereas witches were pagans, and followed the Old Gods. Hence the witch cult was fiercely persecuted, while ceremonial magic was sometimes studied and practised by churchmen. The idea behind ceremonial magic is that of commanding spirits, good or evil, in the names of God and His Angels, and thus making the spirits do your will; and the proof that this is how magicians’ minds worked is to be found in the old magical books called Grimoires, of which the Museum has a large number, both printed and in manuscript. The procedure laid down in them is complicated, and required a certain amount of

education, often involving a knowledge of Latin and Hebrew, to understand it. Also, the rites they specify needed costly equipment, such as swords, wands, magical robes, pentacles of silver and gold, etc. Hence it was only members of the upper classes, or of the learned professions, who could work such rites.

Ceremonial magic originates in the magical rites of the Abrahamic traditions and is historically evolved from the grimoire traditions of the early medieval period. The earliest grimoires invoke the name of the Abrahamic God, his angels and demons, as well as classical Gods, Goddesses, spirits, beasts, mythic figures and garbled language for all manner of purposes.

The witch cult, on the other hand, was something much closer to the soil, its practitioners could be, and probably most often were, completely illiterate. It is the remains of the original pre-Christian religion of Western Europe, and its followers possessed traditional knowledge and beliefs which had been handed down by word of mouth for generations. In spite of the great persecutions (some grim relics of which, in the form of instruments of torture and execution, are preserved in the Museum), the cult has never died. Some remnants of it still exist to this day and the Director of this Museum has been initiated into a British witch coven.

Gardner clearly tries to draw a distinction between Ceremonial Magicians and the Witch Cult. He defines Ceremonialists with wealth, education, professionalism, and sophistication. Witches he defines as more down to earth, rural, illiterate, with oral traditions handed through generations. This is a common stereotype of definitions of “high” and “low” magic which is often viewed as: high magic, gendered male-ceremonial and sophisticated, and low magic, gendered female-witch and primitive.

Magic is the art of attempting to influence the course of events by using the lesser-known forces of nature, or by obtaining the help of supernatural beings. Doing anything for luck, or to avert bad luck, is a form of magic.

Throughout history, magic has exercised a great influence on human thought. Stone Age cave paintings and statuettes show that the ancient people of Europe practised magical rites. They made images of animals on the walls of their caves, and depicted them with spears or arrows thrust into them; it is thought that this was intended as a spell in order to gain power over the animals in real life. The same principle is at work in the old spell of making a wax image of someone and sticking pins into it, in order to do them some harm, which is practised to this day.

Fertility magic became increasingly important with the discovery of farming. Magic then was chiefly to ensure good crops, increase in flocks and herds, good fishing, and many babies, in order to keep the tribe strong. From the days of the first rites in the caves, there is evidence that dancing, magic circles, and fires, were part of magical practice. Later, people began to learn the use of herbal remedies, drugs, and poisons (the latter being useful for killing wolves). Each tribe would have its “wise man” or “wise woman,” probably people with natural psychic powers. This is the origin of the word “witch”; it is derived from an Anglo-Saxon word Wica, meaning “The Wise Ones.” The earliest magic was for the benefit of the whole tribe; later “private magic,” such as love charms, or spells to obtain personal desires, began to develop.

Again, Gardner’s theories are contemporary with his time period.

SORCERY originally meant “to cast lots.” The word comes from the late Latin sortiare. It is an ancient and universal practice to gather a number of objects, such as marked stones, or bones, assign different meanings to each, cast them on the ground, and “tell fortunes” from the way in which they fall. However, the word “sorcery” has come to mean almost any sort of magic.

RITUAL MAGIC, Art Magic, or Cabalistic Magic, seems to have evolved from Egyptian and Babylonian magical beliefs that there were many

great spirits, minor gods, angels and demons, who could be bribed or Impelled to cause events to occur, by means of long rites and conjurations, with or without blood sacrifices. A very important branch of this magic was to know the Names of Power, by which such beings could be summoned and controlled. When used for good purposes, these practices were called White Magic; but if for evil purposes, they were called Black Magic. This last term is nowadays much abused, being often applied to anything occult. We have illustrations, by means of books, pictures, and actual instruments and objects, of all of these types of magic in the Museum.

ASTROLOGY aimed at discovering what the future was likely to be from studying the stars. Its basis is the old Hermetic axiom,”As above, so below.” It is still widely believed in, and is the mother of Astronomy. We have some examples of the tools, books, etc., used by astrologers.

ALCHEMY aimed at finding the Philosophers’ Stone, which would turn all other metals into gold, and the Elixir of Life, which would cure all diseases and prolong life indefinitely. It was the mother of modern Chemistry; though alchemists expressed their art in a curious mystical jargon, to prevent their secrets being stolen. We have some objects and manuscripts relating to Alchemy, but regret we have no Philosophers’ Stone or Elixir of Life to show you.

NECROMANCY was attempting to compel the spirits of the dead to return and give information. It was usually performed with the corpse of a person recently dead. Spiritualism has been attacked as being Necromancy, but this is false, as there is no attempt to impel the spirits to communicate, and no dead bodies are used. We have some pictures of the practice of Necromancy.

PACTS WITH THE DEVIL. We have copies of what are alleged to be pacts with the devil, and other diabolical papers, including the alleged signatures of various devils, from the French National Archives and other sources; but we think the originals were either forgeries or cheats to deceive the simple-minded.

DEVIL WORSHIP is usually regarded as meaning the worship of Satan. We have some relics which are said to have been used in such rites; but we have no real evidence that the people who used them were more than jokers in rather bad taste. Witches have been accused of “devil-worship”; but the Old Horned God of witchcraft is pre-Christian, and “the devil” is a concept of Christian times.

THE BLACK MASS. Many practices which may or may not have taken place have been denounced by this name; but there is little convincing evidence of its real existence. However, we are always willing to receive proof, and the Museum has some objects alleged to be associated with it.

Gardner’s brief descriptions are exactly that and not meant to be definitive in any way. These are introductions to little known subjects for the entertainment, and humour of the tourists.

We have in this Museum the following Exhibits:

On the first floor are two rooms. One represents a Magician’s Study, of the period circa 1630, with everything set out for performing what is variously called Ritual Magic, Cabalistic Magic, Ceremonial Magic, or Art Magic; these terms mean very much the same thing, though some writers use one and

some another. There is a large and complicated circle drawn on the floor, and an altar made to certain Cabalistic proportions. Beside it is the magician’s consecrated sword, and behind it two columns, with a light upon each. If used for good purposes only, this kind of magic was called White Magic; but if used for evil or selfish purposes, it was called Black Magic. The latter might involve the use of blood, and the summoning of demons, who were kept at bay by the Divine Names written around the circle, and were only permitted to manifest in the Triangle of Art drawn outside the circle, where they could be commanded to do the magician’s will.

The other room represents a Witch’s Cottage, with furnishings of about the same date as the above, and with the witch’s magical implements set out for use, with the circle, the altar, etc. It will be seen that these are much less elaborate than those of the magician. The room is an ordinary living-room, with a bed in the background, and a few domestic articles scattered about; the altar is a chest; the circle is a simple chalk line. At an alarm of danger, everything could quickly be made to look quite normal.

The witch’s altar is set out as if for an initiation ceremony. One of the objects upon it is a necklace, the only “ceremonial garment” a witch needed; whereas the magician might wear elaborate robes.

The Exhibits again follow Gardner’s earlier stereotypes of High vs Low magic. (Magician’s Study vs Witch’s Cottage). The manikin in the Magician’s study highly resembled Gardner.

In the First Gallery starts the famous collection of objects connected with Magic and Witchcraft.

Here follows the high point of the Witches Museum! The Galleries!!!

I will not go into lengthy detail as these descriptions are beautifully descriptive however, I will say that the objects on display were both owned by Williamson and Gardner respectively, as well as many items that were ‘on loan’ to the museum, crafted by artisans, previously used by witches and magical people and brought to the museum through their individual contacts. Some were ‘real’ and many were contrived for tourist entertainment.

Case No. 1. A large number of objects belonging to a witch who died in 1951 given by her relatives,

who wish to remain anonymous. These are mostly things which had been used m the family for generations. Most of them are for making herbal cures. The herbs required to make charms or medicines had to be cut at the rime when the moon or the planets were in the particular part of the Zodiac “under the right astrological aspects,” as a practitioner of the art would say; and the curved sickle or “baleen” was used for this purpose. She had a very fine ritual sword, which for many years was lent to the Druid Order which holds the annual Midsummer ceremony at Stonehenge, because it fitted exactly into the cleft in the Hele Stone.

As discussed briefly earlier, this was an exciting period in history when NRMs were being formed in contrast to the oppressive stagnation of Christianity. Besides Witchcraft, Druidry and other pagan religions were being revived. Modern Druidry is also a revived religion of the 18th century.

Case into. 2. A large collection of magical rings and other jewellery, used for the purpose of protection and as luck bringers, and for various other magical purposes. This case contains exhibits illustrating the development of present-day amulets from primitive pagan symbols. There are a large number of “Lucky Pieces,” ranging from the crudely mounted “Badger’s Paw” to intricate and costly astrological jewelry made according to the wearer’s horoscope. Among these is the mediaeval magic ring formerly belonging to the Earls of Lonsdale, set with the fossil tooth of an animal, and surrounded by precious stones. It is a thumb ring made large enough to be worn outside a glove, and was supposed to have a mystic power over its possessor.

Case No. 3. A large number of objects used to ward off the “Evil Eye,” dating from Ancient Egyptian and Phoenician to modern times. The “Evil Eye” is the supposed power to cast a spell upon

another simply by looking at them, ant these mascots were thought to be able in various ways to deflect this dangerous glance. This is probably one of the oldest occult beliefs in the world.

Case No. 4. A representative collection of objects used by witches in their rituals, including a witch’s riding staff, which gave rise to the “broomstick” legend. Its actual use was like that of a hobby-horse, in a kind of leaping dance that was part of a fertility ritual. There are several gazing crystals, and a black concave mirror made by a witch in modem times and consecrated at the full moon in accordance with an ancient formula; all of these are used for “skrying,” as crystal-gazing used to be called the idea being that visions could be seen in them. There is a flask of witches’ anointing oil in a silver case. The case also contains objects used in the witch persecutions, and some relics of Matthew Hopkins, the notorious “Witch-Finder General.” Among the instruments of torture used on witches, shown in this case, are thumbscrews, pincers which were used red hot, and a three-inch-long hand-made pin of the type used to prick for the so-called “Devil’s Mark,” which was supposed to be a spot which would not bleed and was insensitive to pain; also instruments used when witches were burned alive.

Case No. 5. A collection of objects used by witches, given by an existing coven of witches. Naturally, they have only lent articles which they are not using, hence the collection consists chiefly of implements for the making of herbal cures and charms; there is, however, one very fine ritual wand, and a curious old desk containing seven secret drawers, in which they used to hide some of their possessions.

Case No. 6. A large collection of talismans engraved on metal, prepared according to the formulas of the “Key of Solomon” and various other Grimoires. These talismans were consecrated with magical rituals, and had to be made and consecrated under the correct astrological aspects for the object they were to achieve, e.g., to gain someone’s love, to obtain money, success in a struggle, or the cure of sickness, and for many other purposes. The person who wished to achieve some such aim by means of a talisman, after it was made and consecrated, had then usually to wear it next to the skin.

This case also contains a collection of charms used against the “Evil Eye,” mainly Arabic and Italian, and examples of the “Medusa’s Head” charm, which was used to avert evil, and the “Mermaid” and “Sea Horse” charms for the same purposes.

SECOND ROOM:

Case No. 7. A complete collection of the secret manuscripts of the Order of the Golden Dawn, a famous magical fraternity to which Aleister Crowley, W. B. Yeats, and many other well-known people at one time belonged. It was founded by the late Dr Wynn Westcott and S. L. MacGregor Mathers, and claimed descent from the original Rosicrucians. Aleister Crowley quarrelled with the Order and broke away to found his own fraternity. The magical working of the Order of the Golden Dawn is founded upon the Hebrew Cabala, and its Cabalistic knowledge was kept very secret, though some of it has now

found its way into print; but most of the contents of this case have never before been available to the public.

The case also contains a number of documents from various sources, pertaining to other Orders which claim descent from the Rosicrucians.

Case No. 8. A collection of objects used for divination and fortune-telling, and a number of ancient and modern books upon the subject. Also a number of ancient and modem packs of Tarot cards. These cards are the forerunners of our modern playing-cards, but consist of 78 cards instead of only 52, as in the modern pack. They were (and are) much used for fortune-telling, especially by Continental gypsies. The Trump cards have many curious figures upon them, an of which have an occult meaning. Their origin is unknown, and some authorities have postulated that they came from Ancient Egypt. They certainly date back in Europe to 1392, and there are possible earlier references.

Case No. 9. A large collection of pictures showing what people have thought witches looked like, from prehistoric times to the present day; together with pictures of the practice of necromancy, and illustrations of sorcery and dealings with the devil. Reproductions of various pacts said to have been made with the devil some bearing the alleged signatures of demons.

Also some copies of the court records of Manx witchcraft trials, some being of cases which occurred in the close vicinity of this Museum. The latter illustrate the old Manx belief, “If a person is a witch, why shouldn’t they do a bit of witchcraft if they want to ?”.

Case No. 10. A very large collection of books on magic and witchcraft, including a number of ancient manuscripts, ranging from the latter part of the Middle Ages to the present day.

Case No. 11. Types of “killing magic,” including the “Pointing Bone” of the Australian aborigines, and the Malayan “Keris Majapight.” Both of these instruments were used in more or less the same way, namely they were symbolically pointed at an enemy to cast a spell upon him whereby he would sicken and die.

Also some stone implements used as charms for protection against lightning.

Some modern instruments said to enable one to see the human aura, and to gain clairvoyance; together with some instruments used in water divining or “dowsing” of various kinds (the modern term for this being “radiesthesia”).

Also a baby’s caul, used as in amulet to enable lawyers to win cases, and as a charm against drowning. (Charles Dickens mentions this belief in “David Copperfield”). The caul is a membrane sometimes found upon the head of a new-born baby, and sailors in olden times would pay a good price for one, and carry it to preserve them from the perils of the sea.

The case also includes a charm compounded in Naples in 1954, to enable a guilty man to be acquired when tried!

THE NEW UPPER GALLERY:

Case No. 12. A collection of magical objects from

Africa and Tibet.

Case No. 13. Books, letters and personal relics of Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), a famous and controversial figure in the world of occultism; called by some “The Wickedest Man in the World,” and by others “The Logos of the Aeon of Horus.” The collection includes a Charter granted by Aleister Crowley to G. B. Gardner (the Founder of this Museum) to operate a Lodge of Crowley’s fraternity the Ordo Templi Orientis. (The Director used to point out, however, that he had never used this Charter and had no intention of doing so, although to the best of his belief he was the only person in Britain possessing such a Charter from Crowley himself; Crowley was a personal friend of his, and gave him the Charter because he liked him.)

Case No. 14. Various articles illustrating the derivation of the present Arms of the Isle of Man (which are three legs) from the Celtic trisula and similar forms, such as the “Cross of St. Bride,” which were charms for luck and protection, being the signs of ancient gods. (Note: exactly the same device as the present Manx Arms, the “Three Legs,” has been found on a coin from Thrace, dating probably from circa 500 B.C., and upon another coin from Pamphylia, dating probably from circa 480-400 B.C. The Greek name for this device is the “Triskeles”).

This case also contains another collection of objects given by another coven of witches. This includes a horned helmet as used by the male leader in certain rites. Also two most interesting examples of the “Green Man” symbol, sometimes called the Foliate Mask. This was a favourite form of decoration in ancient churches but it actually represents the Old God of the witch cult, the “King of the Woods.” He was called the “Green Man” because he was depicted with leaves-often oak-leaves, -springing from his mouth, or with his face partly made up of leaves, or as if peering through a leafy garland. Some of the oldest examples of the Foliate Mask are horned. The explanation is that the craftsmen who built ancient churches and cathedrals sometimes belonged to the witch cult. They could build no shrines to their private beliefs, everyone being compelled by law to attend the Christian church, but they introduced the Old God into the fabric of the church under this guise, and he became one of the most popular figures for church decoration.

Case No. 15. A number of objects connected with what has been alleged to be “Devil-worship,” Black Magic and the Black Mass; including the form of service used at the funeral service of the late Alaister Crowley when his body was cremated at Brighton on the 5th December, 1947. This was fiercely denounced as being “the Black Mass;” if so, it must surely be the only Black Mass in history to which the Press was invited, and which was fully witnessed and reported by representatives of the local paper!

The case also contains a number of articles lent to the Museum by a magical fraternity, including a chalice used by them in performing Form of Mass for magical purposes. (This fraternity insists, how

ever that this was White Magic and not Black).

Also a magical death-spell, or curse, prepared by the late Austin Osman Spare in 1954. Spare boasted that he could kill anyone by Black Magic (he actually said this in the course of an interview he once gave on radio!). He was an artist, famous for his fantastic paintings

Also a number of other objects used in curious forms of magic, which, if not Black, were certainly extremely Grey. These include a magical lamp which was once the property of the notorious Hell-Fire Club founded by Sir Francis Dashwood in the 18th century. This started as “The Monks of Medmenham,” and was a parody of a monastic brotherhood; but the “Monks” were alleged to worship the devil and indulge in all kinds of licence as their “rule.” Later Sir Francis took his association to his palatial home at West Wycombe, where they carried out their rites in a labyrinth of mysterious chalk caves, now known as the “Hell-Fire Caves,” which may still be seen. The “Hell-Fire Club” was one of the scandals of its day, as many men of wealth and consequence were alleged to belong to it; Sir Francis Dashwood himself was at one time Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Case No. 16. A collection of modern charms and talismans, which people still pay good money for and wear for protection or good luck.

Case No. 17. A few articles used by astrologers and alchemists, and a number of boom upon these subjects.

Case No. 18. A number of books on the subject of magic, and some magical articles.

NOTE: Upon the wall of the Upper Gallery is a large round mirror. This is a Magical Mirror, which has evidently been used by a practising magician or a magical fraternity. It is convex, and backed with a dark substance instead of the usual silvering. Around the frame are the names “Michael,” “Gabriel,” “Uriel,” and “Raphael,” the four great Archangels who are said to rule the four quarters of the universe. Such mirrors as these have been used for many centuries to summon up magical visions

BIBLIOGRAPHY

For introductory research and information on the Witches Mill, Gerald Gardner and Cecil Williamson, I recommend beginning with the following:

Crowther, Patricia, One Witch’s World, (Robert Hale London, 1998).

Gardner, Gerald, The Meaning of Witchcraft, (Aquarian Publishing Company, 1959).

Hesselton, Philip, Witchfather, A life of Gerald Gardner. Vol 1 & 2, (Thoth Publications, 2012).

Howard, Michael, Modern Wicca, (Llewellyn Publications 2009).

Hutton, Ronald, The Triumph of the Moon, (Oxford University Press 1999).

Valiente, Doreen, The Rebirth of Witchcraft, (Robert Hale London, 1989).

VIDEO

This video is an excellent introduction to understanding the witch trials of the medieval period in Great Britain. Enjoy.

This small and unassuming item was once part of a display in the Witches Mill Museum on the Isle of Mann. There were various displays of folk charms, curses and cures.

We feel that it is important to publicly archive some of the items that we own because they are withering with time. That said, there are also many people, who for various reasons, may be interested in these windows of Traditional Witchcraft history and specifically its relationship to Gerald Gardner.

The card is written by an unknown hand and states:

Lucky “Nine Peas in a Pod”,

Take out two peas and hide them on the mantel shelf, place pod with 7 over door and good luck will follow. A long absent unexpected friend will arrive, or may have some unexpected money, or the first man who passes under the doorway will be your husband.

London: Aug 1918.

We hope you enjoy this small perspective of an item once displayed at the Witches Mill.

More to follow…

We cannot go back in time but photos capture precious moments and can give us a visual knowledge of history. These vintage photos were estimated to be taken sometime in the 1960s and can be found in the archives of the Castletown Commissioners, Isle of Mann and in the web photo library. The photographer is unknown.

The Tower, Witches Mill, Castletown, Isle of Man.

The Tower, Witches Mill, Castletown, Isle of Man.

Gerald Gardner is standing in the doorway.

Enterance to the Witches Mill Museum, Castletown, IOM.

Enterance to the Witches Mill Museum, Castletown, IOM.

This is a great photograph and gives us a real feel for what it was like to visit the museum way back when. I like the rustic look and the hand painted signs.

This last photo is of Monique Wilson posing at Ye Old Wishing Well at the Museum.

This last photo is of Monique Wilson posing at Ye Old Wishing Well at the Museum.

ISBN# Volume One: 978-1-870450-80-5

ISBN# Volume Two: 978-1-870450-79-0

I’m very excited to finally have the print copies of Philip Heselton’s crowning achievement in my hands. The ebook has been available from Thoth Publications for a few months and I pre-ordered the print version at that time.

These volumes constitute the definitive history of the early modern Craft and Gerald Gardner’s involvement in it.

I had been given a tip-off that the author had uncovered new research and was able to name the names linking Gerald to the Traditional Witchcraft covines on the Isle of Mann and to document the connection between that interaction and the development of what was to become Gardnerian Wica. So of course that is where I started reading.

As demonstrated by his previous books, Wiccan Roots and, Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspiration, Mr Heselton is a consummate researcher. His exhaustive scope and detail of study combine with his conversational writing style to produce a fascinating and readable history of an admittedly obscure subject. Up front about his position as a Gardnerian initiate, Heselton nonetheless researches and writes honestly, refusing to be selective in his reporting, and not interpreting his data to lead to a particular conclusion. He leaves the reader to decide, based on all the facts available in the source materials.

His deepening research has unearthed much additional material for the new books, making them important additions to the subject of study, even for those who have read Wiccan Roots, and/or The Cauldron of Inspiration. In the event that you haven’t read the earlier books, know that these new volumes will stand on their own as a fascinating study of the most important era in the development of the modern Craft.

Read the Review Here

I’m trained as a stonecarver. Though I carve wood, horn, antler, wax, and I model clay in addition to stonecarving, stone is my favourite material. I love the look, the feel, the weight, the strength and the slowness of stone. I love the natural forms of stone, worked by the elements, as well as those sensitively and skillfully influenced by the hands of humans.

I am enthralled by the relationship my distant ancestors had with stone; the preCeltic, prePictish, neolithic peoples who considered stones worthy of veneration, and committed a disproportionately large amount of their scarce time and population resources to their relationships with these living bones of earth.

The purposes and meanings associated with many of the megaliths have been lost, though physical and astronomical alignments can still be discerned. Folk traditions around the various types of stone monuments attest to magico-symbolic use into the modern era; if those uses have anything to do with the purposes of the original makers, we cannot know.

The purposes and meanings associated with many of the megaliths have been lost, though physical and astronomical alignments can still be discerned. Folk traditions around the various types of stone monuments attest to magico-symbolic use into the modern era; if those uses have anything to do with the purposes of the original makers, we cannot know.

Those megaliths with ancient man-carved or natural holes through them have possessed a particular sanctity throughout history, and have been venerated throughout western Europe for their powers to bless, to protect and to heal. They are found throughout the British Isles, particularly in Cornwall; the north of Scotland, especially the Isles and in Ireland. Examples include the, “Men-an-Tol, Tolvan holed stone and the Merry Maidens holed stone in Cornwall, used for fertility rites and healing and the Kenidjack Common holed stones – unusual in being a group of holed stones in the same location”

(The Megalithic Portal online)

On the Orkney Islands of Scotland and the Isle of Mann, where Scandinavian influence was significant, holed stones were associated with Odin, who in the Eddas passed through a hole in a stone in the form of a worm in order to gain the mead of inspiration. These stones took his name, as in Orkney,

“When visiting the stone, it was customary to leave offerings of food, or ale, and it was common for young people to stick their heads through the hole to acquire immunity from certain diseases. Along the same lines, new-born infants were passed through the hole, in the belief that this would ensure them a healthy future. Crippled limbs were also passed through in the hope of some supernatural cure.”

(Orkneyjar, the heritage of the Orkney Islands website)

Sadly, the Odin stone in Orkney was destroyed by the landowner in the 1940s.

Possibly related to their connection with the god, oaths were sworn at holed stones, with the two parties grasping hands through the hole in the stone. Such an oath was said to have been witnessed by Odin and could not be broken without incurring the wrath of the god. The last vestiges of this practice may have been the small holed stones given by the Deemsters on the Isle of Mann to summon people to court up until the mid 1700s. (The Uses of Rocks in the Past, Manx Mines Rocks and Minerals)

The connection between the two uses suggests that small, portable holed stones may have derived their traditional uses from those of the larger megalithic versions, but on a personal level, rather than functioning for an entire community as the larger versions did. These charmed stones were said to protect those who possessed them from ill luck, disease and bad dreams, and were hung in the home, stable or carried on ones person.

We who follow the old ways may grasp the occult powers of these stones when we realize them as the ontological locus of the Neither-Neither; as lacunae empty of ‘normal experience’; neither in the world, nor in the womb, but in-between. Used properly, they have the power to facilitate a passing through, a leaving behind, a meeting between or an entering into.

As an object of theacentric devotion, holed stones encompass the symbols of both the eternal and bounteous womb of the Earth Mother, and the lithic and fruitless cunt of the Hag. They are holy in both barrenness and in becoming.

These inamoratas of the goddess, when mated with the phallic pole formed the first spindles allowing the metamorphosis of fibre into thread and evoking the eldest of the goddesses; The Three who spin force into form, allot it, and ultimately, deliver it unto Thanatos.

As an aperture to the in-between, gazing through the hole in a stone allows the beholder to see the unseen or otherworldly. Hagstones allow access to the true Dreaming, when used with Art, and protect from being ridden by the night mare while traveling the oneiric realm.

By tradition and experience, each holy stone has its own particular affinity and use, and it falls to the finder to discover the unique talent of the stone. The first holy stone I found was a seeing-stone, and it proved to me the first Samhain after I found it, the efficacy of its powers and my evocations!

I am currently working with two holy stones, both from Ellan Vannin. One I found there, the other is a stone that has been passed down through the tradition with a documented history of use in witchcraft dating back to the end of the 1800s.

Time and Art will tell what use they may make of me…

How Wicca follows Max Weber’s theory and maintains a marginal religious status.

I will briefly discuss how the New Religious Movement (NRM) of Wicca or Witchcraft[1] follows Max Weber’s sociological theory of religious distinction from its popularized founder Gerald Gardner to the present day. This is not to make any claim that Gerald Gardner is the ‘creator’ of Witchcraft but is instead, a gentle examination into its social development. I will demonstrate its evolution from virtuoso to mass religiosity, its integration and transformation within the feminist and Neo-Pagan movements and discuss possible reasons why it remains a marginalized religion in the modern day.

The Father of Wicca – Gerald Gardner

It was 1954 when Gerald Gardner, an elderly charismatic character, with tattoos, wild hair, and a twinkle in his eye first published Witchcraft Today claiming discovery of a witch’s coven that boasted a long and hidden historical lineage. Later Gardner admitted to being a member of the secretive witch-cult[2] and he actively promoted its practice and beliefs through his books and interviews from ‘The Witches Mill’[3] on the Isle of Mann. He initiated women[4] into the cult and they in turn initiated men. The women established their own autonomous covens to varying degrees of success. Regarded as the “Father of Wicca” Gerald Gardner is easily identifiable as Max Weber’s virtuoso who founded what is now known as Wicca or Witchcraft.

The Early Witch-Cult

The early initiates of Wicca, the innovators[5] were attracted to a ‘natural’ mystery religion requiring strong spiritual intensity. Initiation was via opposite gender into the cult and involved nudity, intense vows of secrecy, and the practice of methods which achieved altered states of consciousness to facilitate union with deities or spirits. They involved themselves in the study of sacred texts, folklore and grimoires, copied by hand a Book of Shadows[6], engaged in an oral transmission of knowledge, and specialized in a magical art such as divination, or psychic mediumship. Having no central authority, early Witches had to be self-motivated. Wicca was not for the layperson who awaited a Sunday service but for the uninhibited, who possessed an intense desire for personal gnosis and transcendence. The early Wicca worshipped a Goddess and a God, with the feminine deity primary and lead by a High Priestess and High Priest acting as the deities living embodiments. The love and subsequent sexual union between the deities and initiates was viewed as a healthy and creative aspect of the lifeforce and is celebrated symbolically or actually in the rites. Wicca was extremely socially limited as it broke social norms and taboos by its beliefs and practices. Secondly, the stereotyping of witchcraft with Christian devil worship, black magic, and moral evil, acted as a deterrent for converts.

Even before the death of Gardner, a new witch named Alex Sanders, began to rise from the shadows to greet the public media with his fantastic stories. In the mid 1960s and early 1970s he set out to promote witchcraft and revealed Wicca’s ‘secrets’ to the press in fantastic articles, a vinyl record of the Book of Shadows, and starred in two documentary films[7]. The tabloids revelled in sensational stories of black magic, nude orgies, cult control, Satan worship, psychic powers, and dramas that supported the existing discriminatory stereotypes of witchcraft with immorality an evil. Witchcraft-styled publicity stunts by various actors impelled other notable priests and priestesses of Wicca to publish ‘truth-telling’ novels and articles[8] in defence of Witchcraft, to set the public record straight and to denounce others. This publicity battle between covens and their struggle to ‘clean up’ Wicca’s image, created the foundation for Wicca’s availability to the public and by the mid 1970s self-proclaimed Witches and covens began appearing in both Europe and the Americas. Arguments over lineage and authenticity between Witches assisted in the routinization of Witchcraft. The Book of Shadows which was formally written down by hand from one initiate to another became a method of verifying authenticity. Formalized laws were established that derived from Gardner or Saunders covens. These laws established the hierarchy within coven systems with the Goddess of the Wicca as the primary deity and the High Priestess holding the highest position of authority. The laws also instituted methods of punishment and control, and threatened to curse initiates who broke them to contain rebels within Wicca.

Cult to Sect – Feminist Early Adaptors of Wicca

The 1960s had set fire to the Women’s Liberation Movement, including social justice, equality and rights. Many women were searching for a newer, stronger feminine identity. Groundbreaking feminist researchers, sociologists, archaeologists and academics of various backgrounds such as Gerda Lerner, Mary Daly, Merlin Stone and Marija Gimbutas, were discovering and publishing evidence of goddess worship and challenging textbook his-tory of the world with her-story. Many feminists outright rejected the submissive role imposed on them by patriarchal religions throughout history and began to confront religious dogma and discrimination. With Wicca’s prominent worship of a goddess in its structure and a High Priestess as not only her representative but as the spiritual guide and ruler of a coven, it was ripe for new blood in the feminist movement. In the early 1970s Zsuzsanna Budapest founded the first feminist witches coven called the Susan B. Anthony Coven Number l[9] and by 1975, she had inspired feminists around the world to rekindle goddess worship with her first book The Feminist Book of Lights and Shadows. Witchcraft and the goddess went full force into feminist her-story and women began creating their own Witchcraft rituals, reforming the existing tradition as an alternative to the dogmatic and feminine-suppressive religions of the globe and identifying the Goddess with the ‘Earth Mother’ of all planetary life. Notable in the feminist movement was Starhawk[10] and her 1979 book The Spiral Dance. In 1982 Starhawk, along with Diane Baker, created a Witchcraft fusion of goddess worship with environmental and political activism named the Reclaiming Collective[11]. This second reformation placed Wicca as a ‘green’ religious practice and attracted early environmentally focused men and women. By now, Wicca appealed to various groups outside of mainstream society and became intimately linked with earth based spiritualities, lesbian and gay rights, the women’s movement, and social marginals of many walks of life (Howard, 232-237).

Wicca for the Masses – Communication and Transformation

By the late 1970s and early 1980s Wicca had evolved to become a notable minority religion with a leading role in the evolving NRM Neo-Paganism[12] which existed within the even larger New Age Movement[13]. By the mid 1980s and onward, Wicca not only opened its doors, it opened occult shops, Churches (sometimes renamed Temples), pagan-moots, on-line message boards, open rituals for the public, ‘how to’ type books, on-line training, and spread to multiple variations as unique as the practitioners themselves. Wicca came to the masses and was now designed for the masses by the authors and lead actors in the movement. The extent of personal intensity of spiritual experience in Wicca is now a matter of choice and is dependent on the social networks or absence of networks, the individual practitioner is attracted to. One could be a witch by simply reading Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner, written in 1988 by Scott Cunningham or alternatively by finding a coven who’s members support similar ideals and beliefs of the seeker essentially forming a peer group structure. I suggest that globalization, equal rights movements, democracy, and legal protection under the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights[14] gave Wicca’s religious actors the courage to come out of the broom closet on an even wider scale to the general public and now is on the verge of moving towards Richard Bulliet’s early adapters stage of growth.

Satanic Stereotypes

Old habits die hard and witchcraft’s iconic negative stereotype is still fanned by mass media’s capitalization[15] on sensationalizing people’s fears. As well, the archetype of the witch as a worshipper of Satan and evil incarnate, is promoted by fundamentalist Christian groups that instil hatred toward non-believers. Scriptural texts of the monotheistic faiths react negatively to witches and their orthodox followers continue to hold animosity and outright hostility toward even the term ‘witchcraft’. Witchcraft is often mistaken for the antagonistic Christian movement of modern Satanism[16] that is also a part of the Neo-Pagan movement and rose to popularity in the 1960s. Though feminists have ‘reclaimed’ the title ‘Witch’ to empower them against the perceived misogyny of monotheistic religions, it has not yet had an effect on deep seated discriminatory beliefs within the patriarchal religious systems.

Existing Diversity

Presently Wicca includes Traditional Witchcraft which is the founding initiatory traditions descended from Gerald Gardner and eclectic groups such as Dianic, Solitary, Celtic, Faery, and LGBT Wiccan groups, just to name a few. As Wicca struggles to reach mass religiosity, it has transformed for public appeal. Initiations are no longer necessary; few worship skyclad or perform anything resembling what Gerald Gardner and others promoted in the 1950s. Some new brands of Wicca appear to be similar to fantasy role-playing, LARPing, and historical reconstructional styles of spirituality that embrace anyone who wants to dress like a witch or call themselves one. The complexity of Wicca now includes those who enjoy the malefic witch stereotype to practitioners offering healing and promoting a ‘harm none’ ethic. The lack of a central authority and Wicca’s autonomy has promoted Wicca’s creativity and diversity.

The Great Divide – Traditionalism vs. Eclecticism

Some Traditional practitioners have felt threatened by the liberal developments of Wicca as they struggle to retain their intensive practice. Eclectic Wiccans are reaching out to new members, creating new rituals and claiming they harm no one by defining their own brand of Wicca. Various message boards illustrate the debates between the two fractions of Wiccan believers. Arguments of lineage, politics of authority and authenticity, ethics, practice and historical accuracy continue to be engaged. These debates reflect Weber’s Sect vs. Church dynamic where the original members of the movement resist change and the pragmatics want to open the doors even wider to the masses. I suggest that the in-fighting within the tradition also contributes to its marginal status because it contradicts Wicca’s spiritual messages and deters potential membership. (Coco & Woodward, 479-504)

The early cult of founder Gerald Gardner and his disciples who attempted to routinize the tradition demonstrates Weber’s early sect. The transformers of Wicca, the early adapters, feminists, environmentalists and others who redefined Wicca to suit the individual and communicated its philosophies on a wide scale demonstrate the evolution of Wicca to Weber’s Church or mass status. Wicca remains a marginal religion inclined to small groups of people. Social stereotypes associated with the term ‘witch’, in-fighting, and its eclecticism continue to keep Wicca on the edge of world religions.

Example of the early Witch Cult: Sect

Sect

Above, a photo of the early innovators of Wicca. Here, a coven and a young Alex & Maxine Saunders celebrate a full moon ceremony. Photo credit of Jack Smith, January 1966.

Example of modern Wicca: Public church

To the left, a photo of a modern Wicca circle now modified for the public. Here a coven celebrates a ‘Handfasting’ which is a Wiccan wedding ceremony. Photo credit of Important.ca: Religion and Spiritual Resource Beliefs Resources. http://www.important.ca/wicca_religion_covens.html

BIOGRAPHIES:

Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, Beacon Press, 1992.

Crowther, Patricia. One Witch’s World. London, Robert Hale, 1998.

Farrar, Stewart. What Witches Do: The Modern Coven Revealed. New York, Coward, McCann & Geoghegan Inc. 1971.

Gardner, Gerald. Witchcraft Today. London, Rider, 1954.

Heselton, Philip. Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspriation: An Investigation into the Sources of Gardnerian Witchcraft. Berks, Capall Bann Publishing, 2003.

Heselton, Philip. Wiccan Roots: Gerald Gardner and the Modern Witchcraft Revival. Berks, Capall Bann Publishing, 2000.

Howard, Michael. Modern Wicca: A History from Gerald Gardner to the Present. Minnesota, Llewellyn Worldwide Publications, 2009.

Hutton, Ronald. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kurtz, Lester R. Gods in the Global Village: The World’s Religions in Sociological Perspective, 2nd Edition. London, Pine Forge Press, 2010.

Molloy, Michael. Experiencing the World’s Religions: Tradition, Challenge, and Change – Fourth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. New York, Harper & Row, 1982.

Valiente, Doreen. The Rebirth of Witchcraft. London, Robert Hale, 1989

JOURNALS:

Coco, Angela and Woodward, Ian. Discourses of Authenticity Within a Pagan Community: The Emergence of the “Fluffy Bunny” Sanction. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, volume 36, Number 5, October 2007, pp 479-504.

Fine, Gary Alan. Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America. Journal of American folklore, volume 122, Number 483, Winter 2009, pp 103-104.

Pearson, Jo. Resisting Rehtorics of Violence: Women, Witches and Wicca. Feminist Theology Journal, Volume 18(2), 2010, pp. 141-159.

[1] When witch or witchcraft is capitalized, it is in reference to the religion of Wicca, when lower case, it is the generalized noun or a descriptive.

[2] Witch-cult was the original term used by Gerald Gardner in his writings. As well, Wicca was originally spelt with only one ‘c’ by Gardner however, I use two as it is presently spelled in this format.

[3] The Witches Mill was first owned by Cecil Williamson a practicing witch and Cunning Man. Gerald Gardner purchased the Mill from him. It was alreadys a witch focused museum, restaurant and meeting place prior to Gardner.

[4] Notably, the well known Priestesses of the Witch-cult initiated by Gerald Gardner are Patricia Crowther, Doreen Valiente, Eleanor Bone and Monique Wilson. All four were inheritors of Gardner’s estate.

[5] The term ‘innovators’ is in reference to Richard Bulliet’s early ‘convert pool’ definition of the early minority who joins a budding religion.

[6] A book that every witch initiate must copy. It contains how to practice, lore, rites and observances, spells, and magical correspondences. Each witch tends to personalize it.

[7] The two documentaries are ‘Legend of the Witches’ (1970) and ‘Secret Rites’ (1971)

[8] The early Innovators such as Patricia Crowther, Doreen Valiente, Robert Cochrane, Cecil Williamson, Eleanor Bone, to name a few.

[9] Z. Budapest created what she called the Dianic witchcraft tradition after the Greek classical virgin goddess of the moon. Men were not allowed membership.

[10] Miriam Simos

[11] Presently titled ‘Reclaiming’ it has grown throughout North America and Europe and includes both men and women.

[12] A diverse and eclectic collection of new religious beliefs usually, though not always involving polytheism and often promoted as a revival of the existing old religions prior to the conquest of Christianity.

[13] The New Age Movement is a spiritual eclectic hodgepodge of Eastern and Western religions, science, environmentalism, philosophy, holistic health and a fusion of multiple individualistic beliefs.

[14] Specifically, I would like to cite Article 18 of the UDHR which states “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

[15] In the 1960s and 1970s, stories about witchcraft always provided a sales boost for the tabloid papers and increased their circulation when they were published” Howard, Michael. Modern Wicca

[16] Created by Anton LeVey